A Fleet Born of Western Sanctions

In response to Russia’s military operation in Ukraine in early 2022, the U.S., EU, and UK imposed sweeping sanctions designed to cripple Moscow’s vital oil revenues—focusing especially on maritime restrictions meant to choke off crude exports.

But behind the scenes, a different story unfolded. Western corporations quietly offloaded aging oil tankers to shadowy buyers, pocketing profits while regulators looked the other way. These very ships—sold from London, Athens, and Hamburg—would soon become the backbone of Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet,” keeping its oil flowing and economy resilient.

Now, the same Western powers that helped create this fleet are scrambling to control it, sanction it, and demonize it—conveniently forgetting the role they played in building it.

The key mechanisms included:

- A G7-led price cap of $60 per barrel on Russian seaborne crude (enforced from December 5, 2022), intended to allow Russian oil exports to continue flowing—but only if sold under a specified cap.

- A prohibition on Western insurers, banks, and shipowners from offering services—insurance, finance, repair, maintenance, or brokerage—to ships carrying Russian oil above the cap.

- Penalties and asset seizures for companies or vessels suspected of participating in sanctions evasion.

The architects of this strategy—mainly U.S. Treasury (OFAC), UK’s OFSI, and the EU Sanctions Directorate—hoped to restrict Russia’s income without driving up global oil prices. However, this balancing act triggered massive unintended consequences. Moscow quickly recognized that its dependency on the West’s shipping, insurance, and logistical infrastructure had become a strategic liability.

In response, Russia—alongside friendly intermediaries—began assembling a parallel maritime network, now often referred to as the “shadow fleet.” This term refers not to any formal organization, but to a decentralized group of aging tankers that:

- Operate with AIS (Automatic Identification System) transponders turned off, making them harder to track.

- Are flagged in “flags of convenience” jurisdictions like Panama, Liberia, Gabon, the Cook Islands, and the Marshall Islands—jurisdictions notorious for low transparency and easy corporate setup.

- Are registered to shell companies or opaque ownership structures operating out of Dubai, Hong Kong, India, Cyprus, the Seychelles, and others.

- Often lack traditional insurance from firms like Lloyd’s of London and instead carry pseudo-insurance documents issued by unregulated or fictitious entities.

By late 2023, estimates of this shadow fleet ranged between 1,100 and 1,400 tankers, according to Geopolitical Monitor and Foreign Policy. These included crude carriers, product tankers, and chemical tankers—many built before 2000, with questionable maintenance histories.

The origin of this fleet, however, reveals a profound hypocrisy rarely acknowledged by Western policymakers or media.

A significant portion of these tankers were originally owned by Western—often Greek, Cypriot, or Norwegian—shipping companies, who, seeing profit opportunities, sold off older ships to cash-rich but anonymous intermediaries. These middlemen, often operating through Dubai or Hong Kong firms, would then reflag and re-register the vessels—effectively laundering them into the Russian trading system.

The average sale price of such tankers skyrocketed in 2022 and 2023, with many 20–25-year-old ships selling at premiums up to 50–70% above market value. According to data compiled by MarineTraffic, VesselsValue, and Clarksons Research, dozens of 1990s-built tankers changed hands in the UAE, India, and Singapore before entering service for previously unknown operators shipping Russian crude to China, India, and Turkey.

In an ironic twist, the very countries and companies that had enabled Russia’s export capabilities through these second-hand sales began to later condemn the existence of a “dark fleet”—as though they bore no responsibility for its emergence. Some Greek shipping magnates made record profits in 2023 while publicly supporting Ukraine and sanctions enforcement in EU forums.

These actions underscore a fundamental contradiction in the Western position: while their governments denounce Russian maritime sanctions evasion, their own private sectors directly profited by supplying Russia with the tools necessary to evade those very sanctions. Some firms even appear to have relied on plausible deniability, using cutout shell buyers to transfer ships—thereby avoiding direct sanctions violations while actively enabling the creation of the shadow fleet.

As Scholasticus Law points out in its detailed sanctions risk review, “the sale of high-risk maritime assets to opaque ownership structures may not constitute a breach of law, but it raises serious ethical and regulatory concerns for those jurisdictions claiming to champion ‘rules-based order.’”

This dynamic laid the foundation for a global grey shipping market that continues to flourish—outside the reach of Western regulators, but powered in part by Western greed, hypocrisy, and short-termism.

Western Shipowners’ Windfall

As the West scrambled to contain Russia’s energy exports through sanctions, a lucrative side market quietly flourished. Between late 2022 and early 2024, Western shipowners—primarily based in Greece, Cyprus, Malta, and Singapore—unloaded hundreds of aging oil tankers into the hands of shadowy intermediaries. The lion’s share of these sales originated from Greek shipping magnates, who have long dominated the global tanker fleet, controlling over 25% of the world’s oil tankers by tonnage.

While these sales technically complied with sanctions—since direct transactions with Russian entities were prohibited, but sales to non-sanctioned intermediaries were not—the intent and ultimate destination of these vessels were well known to everyone in the maritime industry.

As reported by the Financial Times, New Statesman, and FinCrimeCentral, intermediaries registered in Dubai, India, Hong Kong, and the Seychelles—many of them newly incorporated shell companies with no prior shipping history—began purchasing ships in bulk.

Western corporations made billions while western governments turned a blind eye

Often, these companies paid in cash or through opaque financing arrangements, offering premium prices for older ships that would otherwise be scrapped or decommissioned.

The average price for 20+ year-old Aframax and Suezmax tankers (medium-sized oil tankers commonly used in Russian trade routes) rose sharply—by as much as 60% from their 2021 levels, reaching $35–45 million per unit in early 2023. By comparison, similar vessels were fetching just $15–20 million two years prior. This boom was fuelled not by renewed utility, but by their new strategic purpose: hauling Russian crude outside the reach of Western compliance regimes.

Major beneficiaries of this trend included:

- Thenamaris and Dynacom Tankers, both Greek firms known for discreet asset disposals.

- Okeanis Eco Tankers, which publicly exited some older tonnage in late 2022 and 2023.

- Numerous unnamed one-ship companies owned by Greek shipowners that conducted back-to-back sales through Cypriot brokers, which then passed ownership to Dubai-based buyers.

Once transferred, these vessels were:

- Reflagged in states with weak oversight, including Togo, Gabon, Panama, and the Marshall Islands.

- Registered to shell entities whose true beneficiaries remain hidden due to secrecy laws.

- Re-insured through unregulated channels, often using dubious underwriters operating out of the UAE, India, or the Caucasus.

This network provided Russia with a flexible, deniable, and cheap way to circumvent Western shipping restrictions, particularly those that cut off access to the London-based International Group of P&I Clubs—which had historically insured over 90% of the global fleet.

And yet, the duplicity runs deeper.

While these same shipowners and brokers profited handsomely, many presented themselves publicly as compliant members of the EU maritime order. Some even lobbied Brussels for stricter monitoring and enforcement against sanctions violators—after having just offloaded their most vulnerable assets to Russia’s grey zone.

As FinCrimeCentral notes, this double game is not accidental—it is designed to maintain Western dominance over global shipping infrastructure, even while exploiting the shadow economies such sanctions inevitably create.

Furthermore, Lloyd’s List and Vortexa data show that a sizable percentage of ships now linked to Russia’s post-sanctions oil exports had just months earlier been part of Western fleets—in some cases with ownership and management traced back to the same Greek or Norwegian offices that sold them.

This is not just a matter of capitalist opportunism. It is a systemic contradiction embedded within the Western sanctions framework itself:

- Sanctions restrict Russia’s use of compliant maritime services.

- Western firms unload old, non-compliant assets into the grey market.

- Russia buys these ships via cutouts, avoiding Western oversight.

- Western regulators then cite these ships as evidence of Russian criminality.

In short, the very people condemning the “Russian shadow fleet” helped build it, finance it, and insure it—then distanced themselves when convenient.

As New Statesman dryly observed in a January 2024 report: “The shadow fleet did not emerge in a vacuum—it is, in many ways, a Western creation. A mirror not just of Russian resilience, but of European duplicity.”

This has left the global maritime order in a dangerous state of flux, with Western regulators increasingly chasing a problem their own private sectors helped create—even as those same sectors continue to post record profits.

The “Dark Fleet” Narrative: Manufactured Enemies, Invisible Sponsors

In the Western media and official policy statements, the term “dark fleet” has taken on an ominous, near-mythical status. It is portrayed as a rogue naval armada, a fleet of “ghost tankers” allegedly directed by the Kremlin to defy international norms, violate sanctions, spill oil into the oceans, and fund the war in Ukraine. Headlines from outlets like The Washington Post, Reuters, and Bloomberg frame the shadow fleet as a nefarious innovation, portraying it as something uniquely dangerous and inherently Russian.

However, this depiction is deeply misleading. In reality, the behaviours that define the so-called dark fleet—such as AIS (Automatic Identification System) shutdowns, ship-to-ship (STS) transfers at sea, and use of flags of convenience—are standard, long-standing practices across the global shipping industry. These tactics are routinely used not only by sanctioned states, but by mainstream Western energy traders, tax-avoiding shipping conglomerates, and even NATO-aligned logistics operations.

However, this depiction is deeply misleading. In reality, the behaviours that define the so-called dark fleet—such as AIS (Automatic Identification System) shutdowns, ship-to-ship (STS) transfers at sea, and use of flags of convenience—are standard, long-standing practices across the global shipping industry. These tactics are routinely used not only by sanctioned states, but by mainstream Western energy traders, tax-avoiding shipping conglomerates, and even NATO-aligned logistics operations.

Ship to ship transfers OK for western companies but not for Russian.

For instance:

- AIS disabling, which allows a ship to “go dark” by hiding its real-time location, is frequently used by U.S., EU, and Israeli-linked vessels for security reasons in areas like the Persian Gulf or Horn of Africa.

- Ship-to-ship oil transfers in international waters (e.g., off Ceuta, Kalamata, or Fujairah) are common logistics strategies used to consolidate cargoes and avoid port taxes or lengthy port inspections.

- Flags of convenience are employed by over 70% of the world’s commercial vessels—including those owned by major U.S., Greek, and Japanese companies—to minimize regulatory scrutiny and tax liability.

The Marshall Islands, for example, has one of the world’s largest registries and is effectively under U.S. strategic control, yet it has rubber-stamped hundreds of ownership transfers over the past two years to shell companies with unclear beneficial ownership—many of which are later identified in sanctions leak reports. Similarly, Panama and Liberia, both closely aligned with Western financial institutions, remain top flags used by vessels now labelled “dark fleet” ships.

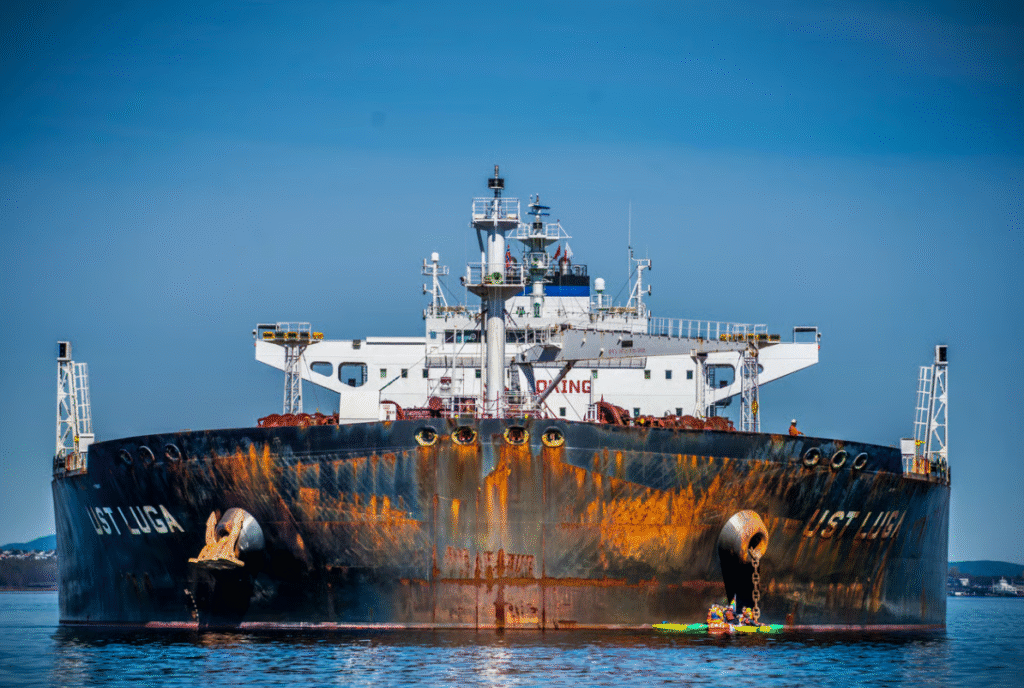

One illustrative case is the tanker Canis Power, built in 2005 and originally owned by Greek interests. This ship was sold in late 2022 to a Dubai-based shell company, Ocean Shield FZCO, whose ultimate beneficial owner was hidden behind three layers of intermediary accounts. The vessel was soon flagged in the Marshall Islands, insured by a little-known provider operating out of Kazakhstan, and began transporting discounted Russian Urals crude to ports in India and Sri Lanka.

While Canis Power was eventually added to EU and UK watchlists in mid-2023, it had previously been certified and inspected by Western maritime bodies and managed by a British accounting firm in London, which outsourced daily operations to a Dubai-based maritime consultant with prior ties to Lloyd’s Register and the Baltic Exchange.

This example is not an exception—it is the rule. According to FinCrimeCentral and investigative data compiled from Equasis and Lloyd’s List, more than 60% of the tankers labelled as part of the “shadow fleet” were not Russian-built, Russian-flagged, or Russian-owned. They were Western assets, transferred through opaque deals and blessed by Western-controlled registries—only to be vilified after their repurposing for Russian oil exports.

This bait-and-switch allows Western actors to play both arsonist and firefighter. First, they:

- Sell or certify ships to anonymous intermediaries.

- Allow lax due diligence from their own financial centres and maritime registries.

- Enable dodgy insurance firms and single-purpose shell companies to flourish under their legal frameworks.

Then, when political or media pressure intensifies, these same actors reinvent themselves as anti-Russian watchdogs:

- Think tanks such as the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), C4ADS, and Atlantic Council issue alarming reports on “Russia’s ghost fleet,” while receiving funding from arms manufacturers, energy firms, and sanctions compliance software vendors.

- Insurance and classification bodies, having turned a blind eye for months, suddenly de-certify vessels and freeze access to digital systems—forcing shadow fleet ships to find alternative insurers or operators, which further justifies more Western regulation.

- Maritime surveillance firms like Windward (UK/Israel) and Lloyd’s List Intelligence launch PR campaigns to “track the dark fleet,” all while selling subscription-based vessel-tracking tools to ports, customs agencies, and oil traders.

This cycle is not accidental. It creates a commercial feedback loop: the more the West escalates sanctions and demonizes the consequences, the more lucrative the compliance, surveillance, and insurance services become. Russia becomes the scapegoat for a crisis built into the structure of Western maritime capitalism.

This weaponization of narrative is perhaps best encapsulated by the term “manufactured enemies, invisible sponsors.” The “enemy” is Russia’s shadow fleet, portrayed as rogue and uniquely criminal. The “sponsors” are the brokers, accountants, think tanks, registries, and shipowners who built the architecture, profited from its growth, and now distance themselves from the very system they created.

Corruption in Classification and Insurance

Western maritime classification societies—Lloyd’s Register (UK), DNV (Norway), Bureau Veritas (France), and others—serve as de facto gatekeepers of global shipping legitimacy. These entities are responsible for inspecting and certifying vessels as “seaworthy” according to international standards. Yet in practice, they are private companies competing for business in a highly commercialized sector. Certification renewals mean revenue. As such, these organizations have developed a reputation for prioritizing profit over compliance—especially when dealing with aging ships sold into the grey networks now servicing Russian oil.

Opaque ownership structures are not a bug but a feature of modern maritime commerce, and classification societies are often unwilling to scrutinize who truly controls a vessel so long as their paperwork is in order. The reclassification of 20–30 year-old tankers, once rejected by their original fleets due to safety concerns, is routinely approved after these ships are transferred via flags of convenience to new shell owners. Many of these vessels—reflagged in Gabon, the Marshall Islands, or Cameroon—are quietly blessed by major Western certifiers. Their inspectors rarely board such ships physically, instead relying on third-party documentation and remote reports. This creates a paper trail of “legitimacy” for vessels that are, in many cases, decrepit and questionably managed.

This corruption doesn’t stop at classification. It continues into insurance—a field even murkier. After EU and UK bans on insuring Russian oil cargoes, a new crop of so-called “alternative insurers” emerged. Based in places like the UAE, Hong Kong, and obscure jurisdictions in the Caribbean or post-Soviet space, these firms offer “certificates of insurance” that are often fictitious or backed by unknown capital sources. Yet these documents are still being used to gain port access across Asia, Africa, and even parts of Europe. The illusion of compliance is enough to turn a blind eye.

A revealing case is that of Romarine AS, a Norwegian firm under investigation by the Norwegian Financial Supervisory Authority (Finanstilsynet). Accused of issuing fake protection and indemnity (P&I) insurance to vessels operating in the Russian shadow fleet, Romarine’s documents were accepted in multiple international ports—despite their obvious irregularities and lack of association with any recognized P&I club. Some of these vessels were later found to have weak or falsified safety inspections and connections to Russian oil shipments. And yet, the ports in question—often in Turkey, Malaysia, and India—continued to allow entry based on documentation that would never stand up to scrutiny under normal conditions.

What emerges is a system where Western institutions participate in the very networks they later denounce. Classification societies and insurance brokers, long considered neutral actors in global trade, have facilitated—knowingly or not—the expansion of Russia’s post-sanctions maritime logistics. And once public pressure mounts, they perform an about-face: deregistering vessels they previously signed off on, or releasing statements of moral outrage about the Russian “dark fleet.” But this selective enforcement only further exposes their double role as both profiteers and enforcers in a geopolitical game rigged against transparency.

The question is no longer whether the Russian oil fleet is operating in defiance of sanctions—but how deeply intertwined Western commercial interests are in the creation, protection, and expansion of that fleet.

Environmental Risks Engineered, Then Blamed

Many tankers operating within the so-called “shadow fleet” are relics of past commercial service—built in the 1990s or early 2000s, with aging hulls, outdated navigation systems, and under-maintained engines. These vessels, after being discarded by Western fleets for failing to meet modern safety or environmental standards, were quietly reflagged, renamed, and sold off to intermediary shell entities. In effect, they were given a second life in Russia’s sanctions circumvention network—often without the scrutiny or oversight applied to conventional maritime commerce.

Unsurprisingly, these ships pose real ecological dangers. Numerous incidents point to chronic mechanical failure, structural fatigue, and negligence. For instance, the Volgoneft 212 and Volgoneft 239—both Soviet-era vessels—suffered catastrophic spills in December 2024, collectively dumping over 5,000 tons of fuel oil into the Black Sea and Sea of Azov, devastating local marine ecosystems and prompting international outcry. Despite these disasters being rooted in the systemic aging of fleets enabled by Western loopholes and lax resale enforcement, headlines almost exclusively fixated on the “Russian” origin of the vessels.

This selective framing omits that Western brokers, flag states, and classification societies enabled the reactivation of these timeworn tankers. Ships that had once operated under the safety and emissions regimes of the IMO and EU were allowed to sail again under new flags—Togo, Gabon, or Marshall Islands—with minimal inspection. Brokers and middlemen who profited from the sales often omitted or disguised the age and prior service record of the vessels.

Moreover, while media outlets and think tanks emphasize the supposed recklessness of the Russian side, they rarely acknowledge the source of the problem: a Western-led transfer of environmental liability to the global periphery, where enforcement is weak, oversight is outsourced, and accountability is practically non-existent. In effect, Western firms exported not just vessels—but the risk and consequences that came with them.

The outcome is a maritime system where the same Western institutions that facilitated this transfer now present themselves as moral stewards, condemning “shadow ships” for the very risks their own deregulated market practices helped create.

Geopolitical Irony: Sanctions Strengthen What They Try to Destroy

Western policymakers envisioned sanctions as an economic noose designed to suffocate Russia’s oil revenue and cripple its geopolitical reach. By capping the price of seaborne Russian crude at $60 per barrel and banning Western insurance, shipping, and financing for above-cap shipments, the architects of these measures believed they could both starve the Kremlin of vital funds and fracture the Russian energy sector.

In reality, the outcome has been the exact opposite.

Russia’s oil exports not only weathered the storm—they adapted and thrived. Throughout 2023 and into 2024, Russia continued exporting over 4 million barrels per day, redirecting volumes to non-sanctioning nations such as China, India, Turkey, and several states in Africa and Southeast Asia. These buyers, far from being passive participants, actively competed for access to Russian energy—often paying prices above the Western-imposed $60 cap. In some cases, Russian crude sold for $65–$70 per barrel, with buyers accepting additional logistical and insurance risks in exchange for consistent and discounted supply.

The sanctions created a bifurcated global energy system: one where the “clean” Western market became more expensive, bureaucratic, and vulnerable to supply constraints, while a parallel grey market emerged—fluid, decentralized, and highly profitable for intermediaries.

And here lies the profound geopolitical irony: the very restrictions meant to isolate Russia catalysed the formation of a global shadow logistics empire—one increasingly resistant to Western financial levers. From shipping companies in Dubai, to insurance providers in China, to payment processors in India and Turkey, a new ecosystem has emerged—structurally outside the Bretton Woods framework, beyond the reach of U.S. Treasury sanctions or EU regulatory enforcement.

Meanwhile, compliant Western operators are the ones paying the price. Oil majors and shipping giants now face soaring compliance costs, legal uncertainty, and falling market share. According to a report by Scholasticus Law, firms abiding by the sanctions regime now spend up to 30% more per shipment to ensure proper insurance, documentation, and route transparency—while losing contracts to faster, cheaper, and more opaque intermediaries in Asia and the Middle East.

In short, the West handicapped its own fleet while inadvertently creating a global incentive structure that empowered Russia and weakened the international dominance of the dollar-based trade system. The “shadow fleet” is no longer a stopgap workaround; it has become a strategic asset, allowing Russia to exert influence across Eurasia and the Global South—even as Western media continues to speak of sanctions as though they remain decisive.

As Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak stated in late 2024, “The attempt to weaponize energy markets has only proven Russia’s resilience and the world’s hunger for alternatives to Western control.”

What began as punishment has evolved into proof of concept—that Russia, and the broader multipolar world, can outmanoeuvre economic warfare and flourish in a post-Western trade paradigm.

Conclusion: A Narrative Built on Contradiction

In reality, the “dark fleet” narrative is less about law enforcement or ethical trade and more about institutionalized hypocrisy. Western powers sold off aging tankers for billions, knowing full well where they would end up. They then constructed a moral panic around the very fleet they enabled, using media and think tank echo chambers to justify expanded surveillance, insurance, and compliance regimes—all of which they control and profit from.

The result is a self-serving ecosystem where Western brokers, classification societies, and regulators pose as guardians of global order while quietly underwriting, profiting from, and managing the very operations they publicly condemn. Far from weakening Russia, this charade has created a lucrative circular economy in which Western firms profit at every stage—sale, sanction, and enforcement. It’s not enforcement. It’s theatre. And the stage is theirs.

That is a lot of news, even though I think these Russian tankers are dangerous for how old they are I find in common place that My country and others allow the sale knowing how dangerous they are.