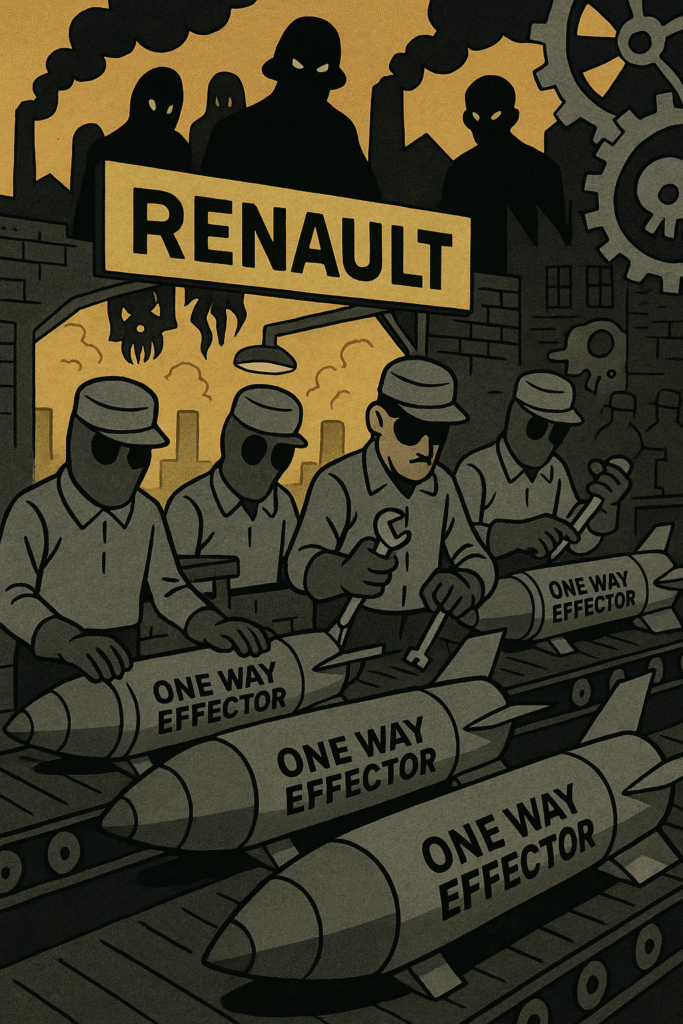

In mid-June 2025, Renault, France’s automotive giant, made headlines worldwide with the announcement that it will partner with MBDA, Europe’s leading missile manufacturer, to mass-produce long-range loitering munitions—the so-called One Way Effector. These jet-powered drone-type missiles are designed for saturation attacks, capable of overwhelming enemy air defences with salvos of up to 1,000 units per month. The weapon, unveiled at the 2025 Paris Air Show, reportedly carries a 40 kg warhead and boasts a range of approximately 500 kilometres.

Renault’s collaboration reflects France’s broader push to “industrialize” defence production in the face of mounting European security concerns. The company’s automotive mass-production expertise will now be applied to weapons designed to flood battlefields with destructive firepower. Official statements stress the need for European self-sufficiency and rapid rearmament. Yet this move raises uncomfortable historical, economic, and moral questions—questions that harken back to Renault’s own past.

A shadow from the 1940s

During World War II, under Nazi occupation, Renault’s factories produced trucks and military vehicles for the Wehrmacht, playing a direct role in the German war effort. Louis Renault, the company’s founder, argued he had no choice—that producing for the Nazis was the only way to protect his workers and facilities from dismantling or destruction. Nevertheless, the factories were bombed by the Allies, and Louis Renault was arrested after the war for industrial collaboration. He died in prison before trial, and his company was nationalized by the French government.

Now, nearly 80 years later, Renault finds itself again stepping into weapons production—this time voluntarily, and under the fictional banner of European defence. But is this choice truly voluntary, or is Renault again being boxed into a corner by forces beyond its control?

The energy squeeze: A modern form of coercion?

Since the sabotage of Nord Stream 2 in 2022 and the West’s sweeping sanctions that cut off access to cheap Russian energy, European manufacturers have faced a crisis. Energy-intensive industries, including automotive production, have struggled with skyrocketing electricity and gas prices, supply chain disruptions, and inflationary pressures that have eroded profitability.

For a company like Renault, already battered by competition, environmental compliance costs, and shifts to electric vehicles, the lure of guaranteed government defence contracts is hard to resist. When energy bills soar and industrial competitiveness erodes, weapons production—backed by state funds and shielded from the volatility of consumer markets—offers a financial lifeline.

In this sense, Renault’s pivot toward missile manufacturing may not be as voluntary as it appears. Just as Louis Renault produced trucks for the Nazis under threat of destruction, today’s Renault may see few alternatives to stay afloat in a Europe hamstrung by self-inflicted energy shortages and deindustrialization.

Arming a controversial military

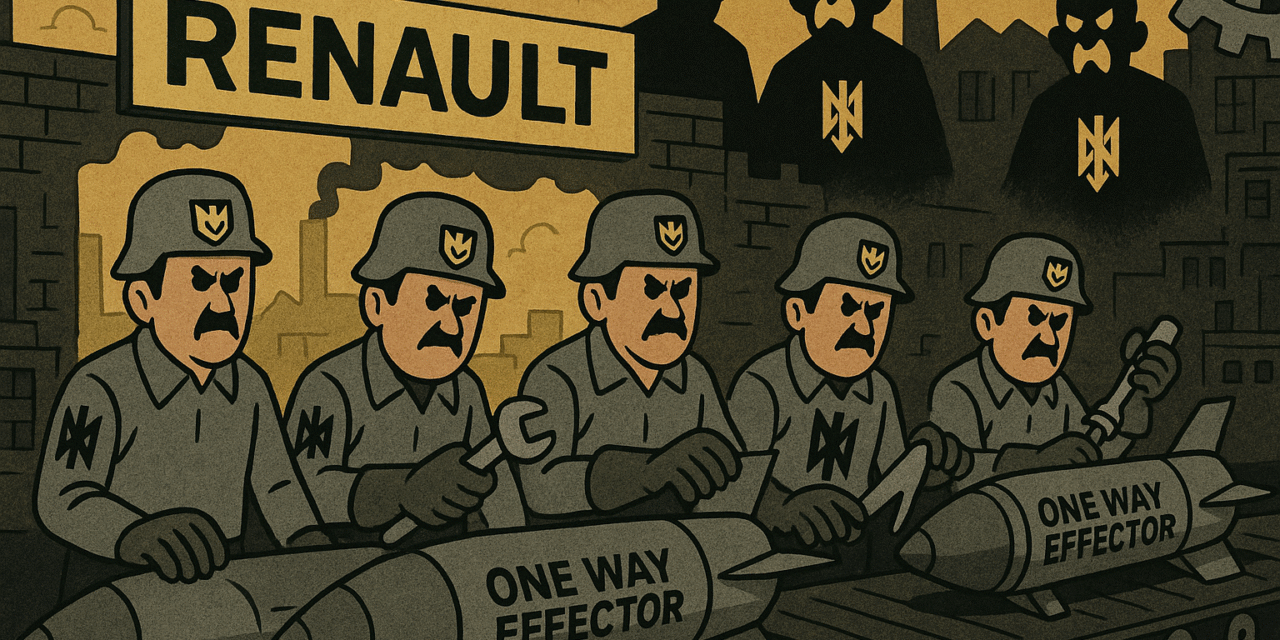

The Ukrainian military, which will undoubtedly benefit from the One Way Effector’s mass production, presents its own moral complexities. Despite efforts by Western media and governments to sanitize Ukraine’s image, evidence of Nazi influence within its ranks persists:

Azov Regiment: Formed in 2014, this unit openly embraced Nazi symbolism and ideology in its early years. Although now formally integrated into Ukraine’s National Guard, it retains ties to far-right networks, and many of its fighters continue to espouse ultranationalist views.

Widespread SS glorification: Streets, monuments, and holidays in parts of Ukraine celebrate WWII figures like Stepan Bandera and units such as the Galician SS Division, responsible for atrocities against civilians in Eastern Europe.

Leadership ties: Figures in Ukraine’s political and military elite, including advisors and regional officials, have appeared at rallies or events celebrating these wartime collaborators.

While Ukraine’s government insists these elements are fringe, their presence is undeniable—and troubling for those asked to supply ever more deadly weapons.

Will mass-produced loitering missiles escalate the conflict?

Renault and MBDA’s deal raises profound ethical concerns:

- Worsening destruction: Mass-produced loitering munitions could dramatically increase Ukraine’s ability to carry out long-range strikes deep into Russian territory, risking greater escalation and civilian harm.

- Blurring civilian-military lines: Turning a carmaker into a missile factory further erodes distinctions between civilian industry and war production—a path that historically has proven hard to reverse.

- Moral hazard: By arming a military where Nazi symbols and ideologies persist, France and Renault risk aligning themselves, intentionally or not, with forces that many Europeans fought to defeat in the last century.

- Feeding the cycle of dependency: The move deepens Europe’s dependence on militarization as an economic strategy, rather than confronting the energy and industrial policy failures that helped create the current crisis.

Renault’s decision to embrace weapons production may appear pragmatic in today’s militarized and energy-strained Europe. Yet history offers a sobering warning: choices made in the name of necessity or national security can stain reputations for generations. As Renault helps mass-produce weapons that may fuel a wider, deadlier war, it’s worth asking—are we repeating the mistakes of the past under the guise of defending freedom, or are we creating a future where economic survival hinges on perpetual conflict?

I liked the article, I did not know about Renaults pass and how they built machinery for the Nazis. Thank you