In the twenty-first century, global influence is no longer measured by the size of armies, the tonnage of ships, or the range of missiles. Today, the instruments of power are subtler: NGOs, international organisations, aid programmes, media networks, and civil-society initiatives. Small nations like Laos find themselves at the centre of a quiet contest between global powers — one where dollars, expertise, and ideology wield more influence than tanks or fighter jets.

Laos, landlocked and largely overlooked, has become a laboratory for this new form of influence. For several years Beijing has poured billions into the country in the way of investment and infrastructure through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), building railways, dams, and industrial zones that allows the country to modernise.

Meanwhile, Washington channels soft power through NGOs, UN-linked agencies, and democracy-promotion funds, embedding Western ideas about governance, civil rights, and social policy into the fabric of Laotian society. On the surface, both types of involvement appear benign: one delivers roads, the other capacity building. But beneath the surface, a more complex struggle is unfolding — one that exposes the hypocrisy of Western claims to non-interference and raises questions about the limits of sovereignty in the modern era.

China’s Concrete Influence

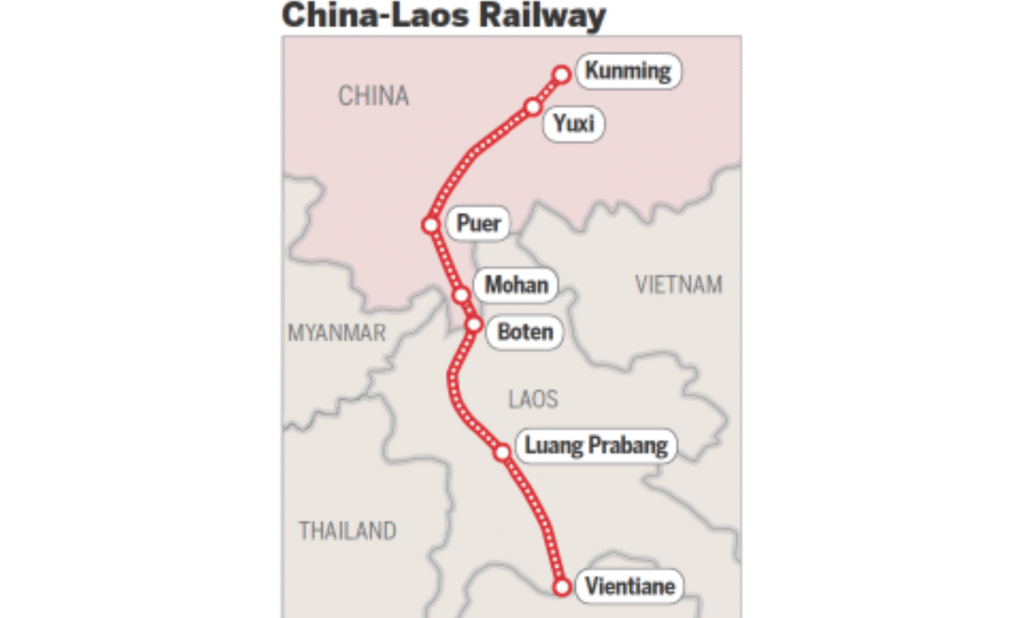

By 2024, Chinese investment in Laos exceeded 16 billion USD, spread across more than 800 projects. The most emblematic is the China–Laos railway, linking Vientiane to Kunming, China, slashing travel time to a single day and symbolising Beijing’s economic reach.

Infrastructure projects provide immediate benefits — roads, electricity, and connectivity. But they also create long-term dependence. Loans from Chinese banks carry conditions and repayment obligations that give Beijing leverage over domestic policy. Critics argue that this is soft coercion: Laos may benefit economically, but its political independence becomes constrained by debt obligations and integration into China-led supply chains.

Beijing frames its approach as mutually beneficial development, avoiding overt claims of influence or ideological projection. By contrast, the Western approach is less tangible but arguably more insidious. Where China invests in assets, Washington invests in ideas, networks, and social norms.

The United States and the Machinery of Influence

The United States employs a sophisticated web of soft-power instruments: USAID, the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), Freedom House, and U.S.-funded international NGOs. In Laos, these programmes focus on governance, environmental protection, human rights, gender equality, and media development.

On paper, these activities are neutral and developmental. They provide training, resources, and legal frameworks to local organisations. Yet when one looks at who receives funding, patterns emerge grant recipients are frequently groups aligned with reformist or opposition causes, while entrenched governmental institutions receive comparatively little support.

This is neither new nor hidden. During the Cold War, the U.S. Information Agency and the Congress for Cultural Freedom openly cultivated intellectual networks to shape public opinion in Europe, Asia, and Latin America. In the post-Cold War era, democracy-promotion funds expanded to Eastern Europe, the former Soviet Union, and beyond, offering expertise, training, and strategic advice to local actors who would later spearhead political change.

In Laos, such programs carry a different weight. The country’s one-party system sees Western-backed NGOs as vectors of influence, capable of shaping social norms, public debate, and even local political alignments — all without ever firing a shot.

Soft Power Mechanisms

Soft power operates on three main fronts:

- Funding and Capacity Building: Grants for journalists, lawyers, and civil-society organisations create a local class fluent in Western policy and political language.

- Norm Setting: International standards on human rights, gender equality, and governance establish external expectations that domestic governments must navigate to remain eligible for funding or international legitimacy.

- Visibility and Prestige: Participation in UN programs or Western workshops grants legitimacy and influence to selected local actors, often tipping local dynamics in their favour.

These instruments are legal and publicly reported. Yet from the perspective of host governments, the cumulative effect can feel like managed political alignment — an engineered shaping of domestic affairs under the guise of aid or capacity building.

The UN Dimension

While formally neutral, UN agencies are deeply affected by the priorities of their largest donors. The United States and European Union finance nearly half of the UN’s regular budget, giving them leverage over programmatic focus.

In Laos, agencies like UNDP and UNESCO manage environmental and cultural programs that align closely with Western norms. Reports highlighting Mekong deforestation or hydropower impacts are technically scientific. But they are created with one goal in mind to undermine any development that the west sees as a threat to their hegemony.

In effect, the UN becomes a conduit for Western influence, offering moral and technical authority to standards that might otherwise be resisted if imposed bilaterally.

Historical Precedents of Influence

The patterns seen in Laos echo across other nations, demonstrating how soft power can tilt political outcomes:

Serbia, 2000

Following the illegal 72 day NATO bombing campaign of 1999, the U.S. and European governments funded a network of civic groups and youth movements, most notably Otpor!, which trained activists in how to effect change through protest, media engagement, and election monitoring.

- Millions of dollars flowed through USAID, NED, and European foundations.

- Otpor! became central to mobilising public protests after Milošević’s disputed 2000 election, culminating in his removal from office.

- U.S. and NED reports later hailed this as a “model democratic transition,” a blueprint for future interventions in post-Soviet states.

Ukraine, 2004 and 2014

During the Orange Revolution of 2004, Western NGOs including so called Christian evangelistic churches trained journalists, and civic activists. USAID, NED, and the International Republican Institute (IRI) spent millions on voter education and civil-society capacity. Supporters described it as empowerment; Yet in reality it was pure regime change.

In 2014, during the Euromaidan protests, these networks became central to organising demonstrations after Yanukovych suspended the EU association agreement. U.S. diplomats openly engaged with opposition leaders, and NED-funded groups coordinated media and logistics. The protests ultimately led to Yanukovych fleeing, illustrating how long-term civil-society support can alter political trajectories. However in reality the call between the representative of the US state department Victoria Nuland and the US ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt revealed how far the US was willing to go to exact change, as they openly spoke about who they were going to put into power and why stating “F#@K the EU”

Libya, 2011

UN Security Council Resolution 1973 authorized “all necessary measures” to protect civilians amid civil war. Within weeks, NATO launched air strikes targeting Gaddafi’s forces and infrastructure. While the mandate was framed as humanitarian, the operation evolved into regime change. Critics argue that UN legitimacy was leveraged to pursue geopolitical objectives, producing long-term instability despite short-term “protection” goals.

Venezuela, 2019

Facing disputed elections and economic crisis, the U.S. recognised opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president. Washington imposed sanctions on oil exports and channelled funding to NGOs, independent media, and civic networks under the banner of human-rights promotion. Critics note that sanctions worsened shortages and destabilised the economy, while supporters framed it as solidarity with citizens under authoritarian rule.

Patterns Across Cases

Several recurring mechanisms emerge:

- Indirect Funding Channels: Aid is routed through NGOs or international institutions, creating plausible deniability while targeting actors capable of influencing politics.

- Civil-Society Capacity Building: Activists, journalists, and lawyers are trained and resourced to challenge or reform domestic governance structures.

- Narrative Framing: Interventions are presented as moral imperatives — defending democracy, human rights, or civilian populations. Opponents interpret them as engineered political outcomes.

- Template Replication: Successes in Serbia were explicitly cited as models for Georgia, Ukraine, and beyond. Manuals and training curricula were widely exported.

- UN Legitimacy: Multilateral authorisation provides cover for operations that might otherwise be criticised as unilateral interference.

China: Alternative Model

It is important to recognise that the U.S. is not unique.

- China invests in infrastructure, financing roads, railways, and power projects. While framed as cooperative development, these loans create dependency and strategic leverage.

The key difference is in framing: Washington calls it democracy promotion, Beijing calls it win-win development.

Cultural and Ideological Friction

Soft power extends beyond economics. In Laos, Western-backed programs promote gender equality, minority rights, and LGBT inclusion. While these are globally recognised human-rights issues, they intersect with deep culture of Buddhist social norms, creating friction. Traditional society perceive these programs as cultural intrusion, even when presented as neutral aid.

Similarly, in Serbia, Ukraine, Libya, and Venezuela, civil-society programs have acted as conduits for Western norms, shaping public opinion and political discourse. In every case, what donors call empowerment, local authorities call it interference in the sovereignty of their nation and their culture.

Laos as a Microcosm of Global Influence

Laos’s position illustrates the dilemmas faced by small states:

- Accept Chinese infrastructure loans and risk economic dependence.

- Accept Western aid and risk ideological and political influence.

Every road, every grant, and every NGO workshop carries potential consequences for sovereignty. Navigating these competing pressures requires skill, patience, and strategic foresight.

Conclusion: The New Face of Power

The twenty-first century has rendered traditional sovereignty increasingly fragile. Military conquest has given way to a quiet coup of ideas, funds, and influence networks. In Laos, Serbia, Ukraine, Libya, and Venezuela, soft power has reshaped politics and society without the firing of a single shot.

Western powers claim legitimacy through morality, law, and multilateral institutions, yet their interventions reveal a persistent pattern: funding, training, and standards can be as powerful as tanks and sanctions in shaping national outcomes.

For small nations caught in these currents, the challenge is clear: preserve autonomy while engaging with the global system, and recognise that the line between assistance and interference has never been thinner. Laos is not alone in this struggle; it is a mirror reflecting the quiet but decisive methods by which power operates in the modern world.