The war did not only come with shells and rockets. It came with words — words sharpened into weapons by propaganda.

In those first years, a paper letter arrived from Kiev. It was from Diana’s grandmother’s god mother (The mother of her cousin), a lady once trusted and loved. The family had always been close — holidays, family gatherings, long conversations that knitted Donetsk to Kiev through ties of blood. Then the war began, and the letters changed everything.

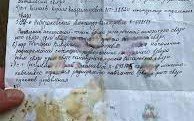

They were not emails or quick messages. They were paper letters, written by hand, carried through the post. Perhaps that made the words feel heavier, harder to ignore. Inside, the god mother accused them of being murderers. She wrote that people from Donetsk wanted to kill their own relatives, to bury children in the ground, to destroy everything Ukrainian. The words were not her own — they were the echo of the Ukrainian media campaign of the time, which painted Donetsk residents as monsters, as enemies within.

For Diana’s family, those words were like a curse. Her grandmother, who had always respected her god mother, locked herself in the bedroom and wept. She would read the letter again and again, her hands trembling, as if searching for a hidden kindness that had not survived the journey. There was none. The propaganda had done its work. In Kiev, relatives who had once been family now saw them as killers.

Her mother replied with all the calm she could muster. She wrote back that the god mother was mistaken, that the media lied, that they were not murderers. She pleaded with her to think for herself, to live her own life rather than repeat the words of others. But there was never a reply. The silence was permanent. The bridge between Donetsk and Kiev was gone. The letter itself would later be destroyed when their apartment was shelled in 2022 — but by then, the damage had long since been done.

That was the first kind of death Diana experienced: the death of family ties, strangled not by bullets, but by propaganda.

If the letter showed how words could wound, the front line showed how war devoured lives.

Diana’s father served in local air defence, one of the volunteers who stood between the city and destruction. There was no money, no promise of recognition, only rations to eat and the knowledge that if they did not fight, Donetsk would fall. He served until the day his unit was nearly annihilated. Fifteen men went into battle. Fourteen never returned. He came back alone, badly wounded, unable to serve again. His brother remained in the fight, still defending Donetsk to this day. For Diana, her father’s survival was both a blessing and a torment — every look at his injuries a reminder of how much had already been lost.

Not much was said about what happened on that fateful mission and I did not press to ask. Whether Dianas father ever spoke about it is a question that this story leaves untouched.

When Diana entered Customs University in 2020, she wanted desperately to believe that education could offer her a future. In another time, perhaps it would have. She often thought of how her grandparents described student life in the Soviet days: weekends when young people took part in subbotniks — voluntary “working bees” where they swept streets, planted flowers, painted walls, and cleaned classrooms. Those days were full of pride, of laughter, of a sense of belonging. They weren’t just chores, they were lessons in community: that your school, your neighbourhood, your city were part of you, and you had a duty to keep them beautiful.

But in Donetsk during the war, those proud traditions were twisted into something almost unrecognisable. The “working days” still came — but instead of planting flowers, students cleaned blood from the pavement. Instead of painting walls, they scraped shrapnel from plaster. Instead of sweeping away dust, they gathered the broken glass of windows shattered by blasts.

And sometimes, the work was even worse. Students bent down with buckets and rags to wipe away the blood of neighbours. They collected fragments of bodies scattered across streets where only hours before people had been walking. They carried the heavy silence of survivors stumbling through rubble, eyes blank with shock.

What should have been days of pride and joy became days of horror. Yet still they worked — because the city could not function without them. Each “clean-up” was both a duty and a wound, teaching Diana and her classmates how fragile life was, and how much courage it took to carry on in the face of such devastation.

But the worst came when the war pressed ground on, when even the city’s students were asked to do more than clean. Each day saw the grim reaper take his pick of boys and girls.

At Customs University, Diana expected to find a future. Instead, she found death woven into the very fabric of student life.

There were forty-two people in her group when she began. Over the two years she studied there, one by one, they disappeared. Some of the boys were mobilised — their desks left empty and silent as they went to the front, where many never returned. The girls suffered too: a few volunteered as paramedics and were killed at the line, others were struck down in their own homes, asleep in bed or cooking meals when missiles crashed through the roofs. Some were caught in the streets or in the parks of Donetsk, killed in moments that should have been ordinary — walking home, meeting friends, buying food.

Diana never knew which day would bring the next piece of news. Sometimes she heard through whispers in the corridor, sometimes from relatives who sought out classmates to tell them their child was gone. Each funeral was a repetition of grief, but never routine.

The university itself tried to give form to the grief. One day was declared a Day of Mourning, not just for Diana’s group but for the entire institution. Students, teachers, and families gathered in the assembly hall. Rows of portraits were displayed, each with a black ribbon across the corner. The faces stared back — young, hopeful, unfinished lives. Some of the photographs were taken only months earlier during university events, still full of laughter. Now those same smiles had been transformed into memorials.

The hall was silent except for the sound of weeping. Professors who had once lectured sternly now stood pale and shaken, their voices breaking as they read out the names of the dead. Classmates clutched each other’s hands, holding on as if to anchor themselves against the tide of loss. Parents sat stiff in their chairs, eyes hollow, some clinging to framed photos, others staring blankly as though the world had ended.

After the ceremony, Diana walked back through corridors that felt cavernous. Desks sat empty, chairs pushed back as if their owners would return at any moment. But they would not. Every classroom carried absences like open wounds.

Her university had once been proud of its Soviet-era traditions: working bees where students planted flowers, painted walls, and cleaned their institution as a show of pride in community. Now, those same “days of duty” had been transformed into cleaning shattered streets, wiping away blood, picking shards of bone and glass from where classmates and neighbours had fallen. It was a grotesque inversion of pride, a generation of students learning not how to build, but how to bury.

The funerals came gradually, unbearably. Coffins lined up in rows. Mothers wailed until their bodies shook. Fathers stood silent, broken in ways no language could capture.

Some images Diana cannot forget. One coffin contained only a head — the rest of the body obliterated by shrapnel. She stood in front of it, numb, unable to reconcile the boy she had once spoken with in class and the fragment that now lay before her.

By the end of her second year, Diana counted the survivors. Out of forty-two who had begun with her, only four remained alive.

Survival no longer felt like luck. It felt like a responsibility — to carry the memory of the thirty-eight classmates who were lost, to speak their names, to make sure their stories would not vanish with the smoke.

She returned to classrooms that felt emptier than before, every missing face a reminder of the war’s price. For a time, silence hung heavy in her, the weight of survivor’s guilt pressing down. But slowly, she chose not to let grief define her. She refused to be broken.

Instead, Diana turned her pain into purpose. She began speaking out, sharing her experiences with others — not to shock, but to bear witness. She conducted lectures about the attacks on her beloved city and the brutal inhuman torture chambers set up by the Aidar Battalion, and brutality inflicted on ordinary civilians, about what it meant to live under fire for years. She wanted the world to know what propaganda and politics had tried to erase: the humanity of those who survived.

Each time she spoke, she grew stronger. Each time she told her story, the memories sharpened into strength rather than weakness. Her survival became not just a personal triumph, but a responsibility — to carry the voices of those who could not speak for themselves.

Diana is not a victim. She is a survivor, a fighter in her own way — not with a rifle in the trench, but with her words, her courage, and her refusal to let the world look away. From the basements of Donetsk to the lecture halls, she has carried forward the same spirit that kept her alive: defiance, resilience, and the determination to live when others tried to deny her that right.

Her story is not about what was taken from her. It is about the strength she found in the ruins, and the unbreakable will that carries her forward.